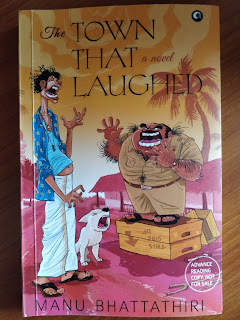

Manu Bhattathiri's 'The Town That Laughed'

In Karuthupuzha, the fictional town of Manu Bhattathiri's novel The Town That Laughed, nobody owns a smartphone. There is no mention of the internet, that ever-ready, inexhaustible source of distractions. Of the two cars mentioned, one is a Jeep and the other an Ambassador. Also, radio seems more favored than tv.

Smartphones and new car models and television are prominent in non-urban India today, so it figures that we are not to think of Karuthupuzha as a contemporary place. In fact, it helps to imagine it as sometime in the 80s, say, when the only channel on tv was Doordarshan; or in the 70s, when radio might have ruled; or in the 60s, even.

Also, the town is ahistorical. In their idioms and phrases and common talk, the townsfolk don't mention any world-historical figure or event. Caste and religious difference are hinted at, but these remain firmly incidental.

In such a town, beset with a timelessness that is both its charm and its malady, Bhattathiri begins with the gambit of change. "Over the past few years much has changed in the small south Indian town of Karuthupuzha," his narrator declares in the very first line of the novel. But these changes can be neither technological nor political, for a stasis on those fronts is essential to Bhattathiri's project. The first change we learn about is that the only bus to Karuthupuzha has been repainted. But where the reader's attention isn't drawn to is the fact that the bus remains the only bus to Karuthupuzha, which is to say that the town's connectivity to the city is unchanged in frequency. A little further, the narrator tells us that now in Karuthupuzha there are "heated discussions on technology and foreign cities and the youth of other lands". But what exactly the townsfolk are discussing isn't revealed. Instead, we learn that these discussions are happening "under banyan trees and behind rustling newspapers." The only temporal hint early on in the novel is when the people arguing "about Western clothes versus Eastern culture" are said to be "growing steadily violent", for somehow this growth seems to the reader as belonging to her own historical moment. But it's a false signal if it is one. All in all, Bhattathiri's enumeration of the changes in Karuthupuzha, including a spectacular segue into a jackfruit tree's sudden fertility, makes for a flourishing opening to the novel but deftly evades any specificity. We are in the hands of a very clever writer.

In the midst of such commitment to timelessness, what change can really be allowed to take place? The answer is generational change: new people taking up the roles occupied by superannuating members of society, who have to slowly and graciously fade away. This change -- the most permanent of changes that there can be in the life of a small-town -- is at the heart of Bhattathiri's novel. Paachu, the police inspector of Karuthupuzha, has retired and has been replaced by a new inspector. His privileges, including the police Jeep, have been taken away. From being the terror of a small town, he has become a part of its senior citizenry. His transformation, from the self-centered, conceited individual who practices his anger in front of a mirror to a man who cries copiously and even comes to empathize with the inveterate town drunk named Joby, is one of the big concerns of the novel.

The other big concern is Joby's health, whose liver is beginning to show signs of damage. To keep Joby off the drink, his friend, Sureshan the barber, looks for a regular job for him. That job is reluctantly granted by Paachu. What does it entail? To accompany Paachu's beloved niece, Priya, to and from school.

Readers of Manu Bhattathiri's brilliant short story collection, Savithri's Special Room & Other Stories, which was also based in Karuthupuzha, might remember Joby and Paachu from that book. They were arguably the most caricaturish characters there (which, for this reader, isn't a bad thing in itself), only sparsely filled with redemptive features, if at all. Joby was the quintessential town drunk who acted like a buffoon and about whom the most generous suggestion was that he had a good heart. Paachu was the monster-like inspector who liked to rule with an iron fist and who, faced with retirement, was assailed by the problem of a stubborn tuft of hair on his balding head, a tuft that would stand erect whenever he exerted himself, making him look ridiculous, though no one in Karuthupuzha could dare laugh at him, no one except his niece Priya.

In The Town That Laughed, Bhattathiri attempts to turn these two into well-rounded characters, for it is only after that that they can believably begin their quest to be well-adjusted. The result is delightful in the case of Paachu who, post his retirement, has become the laughing stock of the town. Increasingly self-aware, it is as if the caricature that was Paachu slowly realizes that he had been missing an entire dimension. This realization, carrying quite a bit of tragic load, makes Paachu wallow in self-pity before he finally shows signs of using this fullness to improve his relationships with others.

In the case of Joby, though, the results are mixed. He is given a backstory: unrequited love. But that story never acquires the urgency that a reader might come to completely care for. Joby's married life, on the other hand, is a taut wire which is surprisingly never plucked. A portrait of his wife, Rosykutty, in which the narrator describes her befuddling compulsion of placing things on edges (literally, like placing a teacup on the edge of a table), is the strongest passage in the book. Not enough attention is paid to Rosykutty, alas, who remains an enigma, and the novel is the weaker for that. But the glimpses we have of Joby's marriage with her do suggest that their intimacy issues are related to their traumas (Rosykutty was an orphan). If so, it is unfortunate that Joby finds himself in a Bhattathiri fictional universe, where psychological exploration can't become too harrowing, where the aesthetic precludes an entry into the darker aspects of interpersonal relationships, where traumas have to remain palatable, where, like technology and politics, sex has to be somewhat in abeyance.

Which transports us to the landscape of larger questions: what is truly at stake in a Bhattathiri story? Is the aesthetic really capable of exploring the convolutions of human nature in Indian small towns in this century?

The answer to the second question is most likely a no, for Bhattathiri's Karuthupuzha is not a proxy for a small town that exists beyond the metropolis today, like Malgudi might have been in its time, but a harkening to the past -- or an anachronism, depending on the point of view. To that extent, its ability to speak to the current times cannot, and perhaps should not, be a prerequisite to its success. So let it be said that The Town That Laughed succeeds on its own terms. It is a very good, very entertaining novel, one that will keep you interested at every page and never let your attention slip; a novel that has an ending that will tug at your heartstrings, one that will evoke a spike of laughter here and tear of sadness there. Yet, if at any time you feel that Paachu's problems in life would go away if he simply connected with old friends over WhatsApp and revelled in dirty / hyper-nationalistic / Islamophobic jokes (like old uncles are prone to doing these days), then the reminder that such connectivity is not available to Paachu, or that such impulses are muted in his personality, might be an adjustment that you have to make. Similarly, if at any point it seems frustrating that Joby's well-wishers, upon seeing him hurtling towards death, would not take him to a hospital but go to great lengths to find a physically-intensive job for him, then you will need to somehow go along with the flow and attribute their actions to the general quirkiness of the place.

With two works set in Karuthupuzha, Bhattathiri has no doubt reanimated a relic, that of the fictional Indian small town, and made space for himself at the top table of Indian writers in English. Rendered in his effortless style that comes with quirky personalizations, Karuthupuzha has the makings of a blessing that can keep on giving. The clever thing, as pointed out above, is that this fictional universe's real-world connections are pliable, such that they are capable of housing a variety of situations and many, many kinds of conflicts. Till now, the conflicts Bhattathiri has chosen are small, and in his two books, he has portrayed them successfully. At some point, though, this reader hopes that he will aim higher and fail.

Comments

Post a Comment